More Evidence of Harm from Smoking During Pregnancy

UTRECHT, Netherlands -- Exposure to tobacco smoke before birth may raise blood pressure substantially in infancy, which could have consequences later in life, researchers here said.

UTRECHT, Netherlands, July 30 -- Exposure to tobacco smoke before birth may raise blood pressure substantially in infancy, which could have consequences later in life, researchers here said.

In a population-based study, infants whose mothers smoked during pregnancy had systolic blood pressure that was half a standard deviation higher than babies not exposed prenatally (5.4 mm Hg, P=0.01), according to a report published online in Hypertension: Journal of the American Heart Association.

That was true even after controlling for potentially confounding factors, said Cuno S.P.M. Uiterwaal, M.D., Ph.D., of the University Medical Center Utrecht, and colleagues.

The findings add to the evidence of harm associated with smoking and tobacco smoke exposure during pregnancy, such as fetal hypoxia and intrauterine growth retardation, they wrote.

"Because blood pressure tracking is stronger from early infancy than from the neonatal phase onward," they said, "it is likely that our findings do have an impact for later-life blood pressure."

Previous studies have linked prenatal smoke exposure to higher childhood blood pressure, but whether the risk was set in utero or after birth by a shared environment was not clear, the researchers said.

So, as part of a larger health project studying Utrecht residents, the researchers conducted a birth cohort study in the unselected population.

The Wheezing Illnesses Study Leidsche Rijn (WHISTLER) included 456 infants with blood pressure, heart rate, chest and lung function measured by age two months and prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal data collected regarding smoke exposure and other factors from 293 mothers and 244 fathers.

Of the mothers, 6.6% reported smoking during pregnancy, 13.8% reported exposure to secondhand smoke, and 79.6% reported no exposure during pregnancy. Maternal and paternal diastolic and systolic blood pressure was not associated with infant blood pressure levels.

Newborns whose mothers smoked in pregnancy were significantly lighter (P=0.03) and shorter at birth (P<0.0001) and had smaller chest circumference (P=0.02) than those not exposed. They were also significantly less likely to be breastfed (P<0.0001).

However, when controlling for these factors, as well as for infant and maternal age, the researchers still found significantly higher systolic blood pressure among infants whose mothers smoked during pregnancy (difference 5.4 mm Hg, 95% confidence interval 1.2 to 9.7, P=0.01) than those not exposed even to secondhand smoke.

The association appeared to be almost entirely accounted for by effects on boys.

Male offspring of mothers who smoked in pregnancy had an 8.6 mm Hg higher systolic blood pressure than those not exposed (95% CI 0.5 to 16.8, P=0.04), whereas no significant difference was seen among girls in systolic blood pressure by prenatal smoke exposure.

"Perhaps gender is a modifier of stress responses in general, including tobacco smoke exposure in pregnancy," the investigators speculated.

Secondhand smoke exposure alone was not associated with infant blood pressure compared with nonexposure (adjusted difference -0.6, 95% CI -3.6 to 2.4, P=0.69).

Nor were there differences in diastolic blood pressure for either smoking during pregnancy (adjusted difference -0.5, 95% CI -4.6 to 3.5, P=0.80) or secondhand smoke exposure (adjusted difference -2.3, 95% CI -5.1 to 0.5, P=0.11) compared with nonexposure.

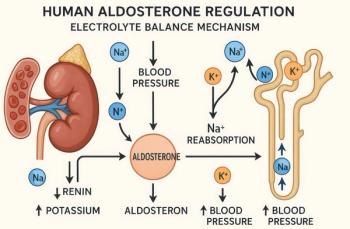

The mechanism for the effects "is basically unknown," the researchers noted.

Animal studies have suggested "an adverse fetal environment as manifested through low relative birth weight has consequences for organ growth in general," they wrote. Another possibility is that fetal exposure causes hormonal or autonomic function changes, they added.

The findings are in agreement with childhood studies, which have also found associations with maternal smoking predominantly for systolic rather than diastolic blood pressure.

"To see whether the effect on infant blood pressure will track into childhood, a follow-up of the relation between smoking during pregnancy and blood pressure in childhood is necessary," the researchers concluded.

Newsletter

Enhance your clinical practice with the Patient Care newsletter, offering the latest evidence-based guidelines, diagnostic insights, and treatment strategies for primary care physicians.