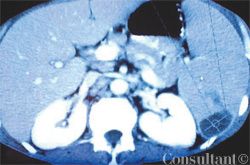

Abstract: In addition to causing pulmonary disease, infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis can result in a wide range of extrapulmonary manifestations, including abdominal involvement. Patients with acute tuberculous peritonitis typically present with fever, weight loss, night sweats, and abdominal pain and swelling. Intestinal tuberculosis is characterized by weight loss, anorexia, and abdominal pain (usually in the right lower quadrant). A palpable abdominal mass may be present. Patients with primary hepatic tuberculosis may have a hard, nodular liver or recurrent jaundice. The workup may involve tuberculin skin testing, imaging studies, fine-needle aspiration, colonoscopy, and peritoneal biopsy. Percutaneous liver biopsy and laparoscopy are the main methods of diagnosing primary hepatic tuberculosis. Treatment includes antituberculosis drug therapy and, in some cases, surgery. (J Respir Dis. 2005;26(11):485-488)