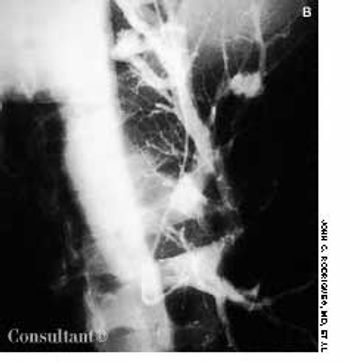

A 63-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with neck pain of 2 days' duration. The pain radiated to her mid back and both shoulders.

A 63-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with neck pain of 2 days' duration. The pain radiated to her mid back and both shoulders.

A 76-year-old man presents with a sudden severe, painless loss of vision in his left eye.

56-year-old man with a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension presents with chest pain, emesis, pallor, and diaphoresis.

A 53-year-old man with a 30-year history of heavy injection drug use (10 to 15 bags of heroin per day) was hospitalized with fever (temperature, 39.2°C [102.5°F]) and chills of 2 days' duration. Infective endocarditis was diagnosed based on the results of 3 sets of blood cultures, which were positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus.

A 54-year-old man with chronic renal insufficiency presented with shortness of breath, nonproductive cough, and chest pain. The patient had hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a 30-pack-year history of cigarette smoking. He denied alcohol or illicit drug use and prolonged exposure to asbestos, chemicals, or fumes.

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a potentially life-threatening complication that occurs in about 1% to 5% of patients who receive heparin.1 Patients with HIT are at risk for the development of new thrombosis, including pulmonary embolism (PE). The mortality rate among patients with HIT and thrombosis is about 20% to 30%.2-5

Chronic diarrhea presents difficulties for clinicians as well as for patients. Because the differential diagnosis is enormous, management can be challenging. In this article, we present a strategy for quickly narrowing the differential based on a simple analysis of stool characteristics. We then describe an appropriate workup for each of the basic types of diarrhea.

For 2 days, a 68-year-old woman had watery, yellowish diarrhea with mucus and left lower quadrant pain. Her medical history included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and congestive heart failure (CHF); she had left the hospital 5 days earlier following treatment of an exacerbation of CHF with intravenous furosemide and sodium and fluid restriction. The patient was taking furosemide, lisinopril, and glipizide; she denied any recent antibiotic therapy.

For 2 days, a 68-year-old woman had watery, yellowish diarrhea with mucus and left lower quadrant pain. Her medical history included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and congestive heart failure (CHF); she had left the hospital 5 days earlier following treatment of an exacerbation of CHF with intravenous furosemide and sodium and fluid restriction. The patient was taking furosemide, lisinopril, and glipizide; she denied any recent antibiotic therapy.

Abstract: Important components of the workup for interstitial lung disease (ILD) include the history and physical examination, chest radiography, high-resolution CT (HRCT), pulmonary function testing and, in some cases, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and/or biopsy. Pulmonary function tests usually show a restrictive ventilatory impairment. However, some patients have a mixed restrictive/obstructive pattern; in fact, almost 50% of patients with sarcoidosis have airflow obstruction at presentation. HRCT has an increasingly important role in the assessment of ILD. In some cases, the results may obviate the need for biopsy. BAL can help confirm the diagnosis of ILD; it also can identify conditions such as infection or hemorrhage or suggest an alternative diagnosis. Surgical lung biopsy has the advantage of yielding samples of lung tissue that are usually diagnostic, especially if HRCT is used to target lung regions. (J Respir Dis. 2005;26(11):466-478)

A cardiovascular risk reference guide, Framingham global risk assessment scoring guide, cardiovascular checklist, and cardiovascular risk-reduction treatment plan.

Five days ago, a 46-year-old woman experienced dull, aching retrosternal pain that radiated toward the left shoulder. The pain was accompanied by diaphoresis and did not abate; she was hospitalized.

Cardiovascular (CV) risk-reduction regimens require comprehensive assessment, patient education, and follow-up, which can be difficult and time-consuming in a busy primary care practice. Moreover, compliance among patients at high risk can be poor. The use of evidence- based risk assessment checklists and patient education materials can enhance care and improve compliance; in addition, thorough documentation can ensure full reimbursement for services.

As many as half of patients who are evaluated for abdominal pain do not receive a precise diagnosis. And for about half of those who are given a diagnosis, the diagnosis is wrong. In this article, I will use actual cases (not "textbook" examples) to illustrate an approach to abdominal pain that begins with a careful differential diagnosis. I also offer some general guidelines for evaluating patients.

A 24-year-old Korean woman, who was 20 weeks' pregnant, was referred to an allergist for an elimination diet and evaluation of the risk of allergies to her unborn child. She had a several-year history of perennial allergic rhinitis with seasonal exacerbations.

In patients with underlying disease, a preoperative evaluation and targeted perioperative management strategies can minimize surgical complications and maximize healing. This article focuses on how to identify surgery patients at risk for complications caused by diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and other medical conditions; I also describe strategies to minimize such risk.

Skin signs of systemic disease: sarcoidosis, rheumatoid nodules, Muir-Torre syndrome, diabetic vasculopathy, hyperlipidemic nodules, zinc deficiency, and Sister Mary Joseph nodule.

Abstract: The coexistence of asthma and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in a given patient presents a number of diagnostic and treatment challenges. Although the relationship between these 2 diseases is complex, it is clear that risk factors such as obesity, rhinosinusitis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) can complicate both asthma and OSA. In the evaluation of a patient with poorly controlled asthma, it is important to consider the possibility of OSA. The most obvious clues are daytime sleepiness and snoring, but the definitive diagnosis is made by polysomnography. Management of OSA may include weight loss and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Surgical intervention, such as uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, may be an option for patients who cannot tolerate CPAP. Management may include specific therapies directed at GERD or upper airway disease as well as modification of the patient's asthma regimen. (J Respir Dis. 2005;26(10):423-435)

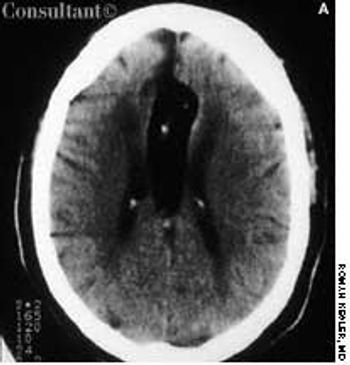

A 62-year-old African American woman was brought to the emergency department (ED) after the sudden onset of slurred speech and weakness in her left arm and leg. Her medical history included hypertension, insulin-dependent diabetes, and congestive heart failure.

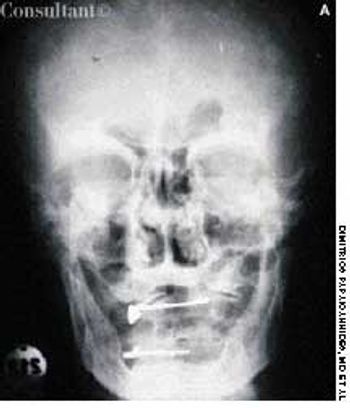

A 74-year-old man, who had been aware of a gradual increase in hat size over the past 3 years, complained of a mild headache and backache. His serum phosphatase level was 1,475 U/L (upper normal limit, 120 U/L). Skull films showed calvarial enlargement caused by thickening of the cortical tables, radiolucency in the frontal and occipital regions, and patchy osteosclerosis that produced a cotton-wool appearance.

Having suffered progressive shortness of breath for 2 years, a 35-year-old man was eventually hospitalized. The patient's dyspnea had worsened over the past year, but he had neither chest pain nor palpitations. His primary care physician first noticed finger clubbing 8 months ago.

A 69-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with wheezing and dyspnea. She also complained of hoarseness and slight dysphagia that had caused a loss of 12 lb during the past 4 months. The patient had been treated for bronchial asthma as an outpatient, but the worsening episodes of wheezing were not being controlled by bronchodilator therapy.

A 63-year-old man was given oral celecoxib, 100 mg bid, for shoulder pain. Three days later, a pruritic rash appeared on his back, then spread to the chest, lower legs, and face. He stopped the celecoxib on his own and self-administered diphenhydramine for the pruritus. The rash and itch persisted, which prompted the patient to seek medical care. He had no respiratory symptoms.

A 45-year-old man with a history of congestive heart failure presented with cough and dyspnea. A chest roentgenogram showed loculated pleural effusion in the horizontal fissure of the right lung, and a CT scan revealed pleural-based density in that lung.

For the past 6 weeks, a 72-year-old woman with a history of ovarian cancer had had intensifying dyspnea. Initially, she thought her breathing problem was caused by progressive congestive heart failure.